Appendix 2

Phase space, statistics and thermodynamics

Statistical mechanics describes a physical system given we know little about its microscopic details. At a first glance, this appears the converse of what we do in molecular dynamics. In molecular dynamics calculations, we have to specify an initial condition, the positions \(\v {r}_i\) and momenta \(\v {p}_i\) (this chapter will use momenta \(\v {p}_i = m_i \v {v}_i\) instead of velocities \(\v {v}_i\)). These initial conditions define the state of the system exactly, which means we know everything there is to know about our molecular system. Note that a single state, as specified by \(\{\v {r}_i,\v {p}_i\}\) is also called a microstate in the context of statistical mechanics. All microscopic degrees of freedom are specified for a microstate.

In most practical situations, we usually don’t have information to this level of detail, and in most cases the results don’t depend on the details of the microstate. In MD calculations, we have to initially guess what a good representative microstate could be. This means while we do know exactly what our microstate is, we don’t really know how representative this would be for the real, physical situation that we want to describe with our calculation. Note that the momenta (velocities) are usually picked randomly because we really don’t know these quantities. However, we do know their statistical distribution. Obtaining this distribution is one of the objectives of statistical mechanics and is discussed in detail below.

Another goal of statistical mechanics is to compute the functional dependence of macroscopic properties, for example the dependence of pressure on volume, \(P(V)\), or the lattice constant of a crystal as a function of temperature, \(a(T)\). Macroscopic properties are expressed as averages over all microstates, weighted by the probability with which they occur. The goal is therefore to reduce the number of degrees of freedom from \(N_A \sim 10^{24}\) to a few. This is sometime referred to as coarse-graining.

Note that we have computed \(P(V)\) for a solid in the previous chapter. This was possible because the calculation was carried out at a temperature of zero. Then, there is no thermal motion and for a single crystal we know the positions (and velocities, they are zeor) of all atoms exactly. Hence there is only a single microstate and we can carry out the calculation by just considering this state without averaging. In most cases, however, we need to compute averages. We will start our discussion of statistical mechanics with details on how averages are carried out.

2.1 Phase space and phase space averages

The positions \(\v {r}_i\) and momenta \(\v {p}_i\) of all atoms define a microstate. This microstate is typically characterized by a \(6N\) (in 3D) dimensional vector \(\v {\Gamma }\) that defines a point in phase space. Imagine we now have an observable \(O(\v {\Gamma })\). The observable gives a certain property as a function of the point in phase space, i.e. as a function of the positions and momenta of all atoms. We have already encountered three such “observables”, the potential energy \(E_\text {pot}\), the kinetic energy \(E_\text {kin}\) and the total energy \(H = E_\text {kin} + E_\text {pot}\). Other examples are the lattice constant \(a\) of a crystal, for example as obtained from scattering experiments or from averaging over the individual bond-lengths of our crystal. Note that the potential energy and lattice constant depend on just position and the kinetic energy on just velocities, so each is constant in large portions of the full phase space.

A phase space average is now obtained from a simple integral over all possible configurations, weighted with the probability of their occurrence, \(\rho (\v {\Gamma })\). The function \(\rho (\v {\Gamma })\) is called the phase space density. Since it is a probability density, it needs to be normalized, \(\int d^{6N} \Gamma \rho (\v {\Gamma }) = 1\). Averages \(\langle \cdot \rangle \) are obtained by \begin {align} \langle O \rangle &= \int d^{6N} \Gamma \rho (\v {\Gamma }) O(\v {\Gamma }) \nonumber \\ &= \int d^3 p_1 d^3 r_1 ... d^3 p_N d^3 r_N\, \rho (\{\v {r}_i\},\{\v {p}_i\}) O(\{\v {r}_i\},\{\v {p}_i\}) \end {align}

and are called ensemble averages. From the knowledge of the full phase space density, we can also compute the variance of fluctuations of this quantity around the average, \begin {equation} \langle \Delta O^2 \rangle = \langle O^2 \rangle - \langle O \rangle ^2 \end {equation} which are a measure for the uncertainty of the quantity. The trick is now to choose the phase space density \(\rho (\v {\Gamma })\) properly.

2.2 Few microstates

For illustrative purposes, we will start by discussing the phase-space density for just a few microstates. We can express just a single microstate – let us call it \(A\) with positions \(\v {r}_i^A(t)\) and momenta \(\v {p}_i^A(t)\) – in this density: \begin {equation} \rho (\{ \v {r}_i\};\{ \v {p}_i\};t) = \prod _i \delta (\v {r}_i - \v {r}_i^A(t)) \delta (\v {p}_i - \v {p}_i^A(t)) \end {equation} Since \(\int dx\, \delta (x-x_0)f(x) = f(x_0)\), or rather \(\int dx\, \delta (x-x_0) = 1\) we have \(\int d^{6N} \Gamma \rho (\v {\Gamma }) = 1\), i.e. the phase space density is a density. Of course, this constructed example does not really express any probability since we have just one microstate. Note that this phase space “density” depends on time \(t\) explicitly since the microstate evolves according to Hamilton’s equations of motion!

As the simplest example of how probabilities emerge in the phase space density, let us consider the (probabilistic) combination of two microstates. Let us call the second state \(B\), then \begin {equation} \begin {split} \rho (\{ \v {r}_i\};\{ \v {p}_i\};t) =& w_A \prod _i \delta (\v {r}_i - \v {r}_i^A(t))\delta (\v {p}_i - \v {p}_i^A(t))\\&+ w_B \prod _i \delta (\v {r}_i - \v {r}_i^B(t))\delta (\v {p}_i - \v {p}_i^B(t)), \end {split} \label {eq:twostates} \end {equation} where \(w_A\) and \(w_B\) are the statistical weights of each of these states. For example, if \(w_A=w_B=1/2\) then both states will occur with the same probability. Note that \(w_A + w_B =1\) to ensure normalization of \(\rho \). Note that \(\rho \) still depends explicitly on time \(t\).

Rather than using two states, we are in most practical situations interested in an infinite number of states. We are also typically interested in equilibrium. By definition, equilibrium is a steady state and hence the time dependence disappears. Therefore, for all cases discussed in the following \(\rho \) will be independent of \(t\).

2.3 The microcanonical ensemble, equal a-priori probabilities and entropy

Equation \eqref{eq:twostates} is the simplest example of an ensemble of microstates, in this case the two states \(A\) and \(B\) that we explicitly specified. Rather than explicitly expressing the microstates through their positions and momenta, we can also ask what the ensemble of state is that belongs to a certain (macroscopic) observable. This ensemble consists of all states that are compatible with this observable. The simplest one is the ensemble of microstates belonging to a certain value of the total energy (or Hamiltonian) \(H\), which is a conserved quantity of the microscopic motion. This ensemble is called the microcanonical or sometimes the NVE (for constant particle number \(N\), constant volume \(V\) and constant energy \(E\)) ensemble.

This microcanonical ensemble is a statistical average over all states with the same total energy \(E\), i.e. \(\rho = \rho (\v {\Gamma };E)\) is a function of the energy \(E\). We know that all microstates \(\v {\Gamma }\) that have total energy \(E\) must fulfill \(H(\v {\Gamma })=E\). How do we now assign probabilities to each of these microstates that fulfill \(H(\v {\Gamma })=E\)? Since we do not know anything about the specific state, we must assume that all occur with identical probabilities. This is the fundamental postulate of the microcanonical ensemble, the postulate of equal a-priori probabilities. We assume that all possible states are equally likely, because we don’t have any information about them, except for the their total energy \(E\). The phase-space density is the given by \begin {equation} \rho ^\text {eq}(\v {\Gamma };E) = \begin {cases} 1/\Omega (E), & \text {if}~H(\v {\Gamma }) = E\\ 0, & \text {else} \end {cases}, \label {eq:rhoeq1} \end {equation} where \(\Omega (E)\) is called the phase space volume. The (constant) factor \(1/\Omega (E)\) is necessary such that the density is normalized. Not that the phase space volume just counts the number of available states, \begin {equation} \Omega (E) = \int _{H(\v {\Gamma }) = E} d^{6N} \Gamma \end {equation} Note that the superscript eq in \(\rho ^\text {eq}\) indicates that we are in equilibrium, i.e. there is no time dependence left.

Equation \eqref{eq:rhoeq1} can be written alternatively as \begin {equation} \rho ^\text {eq}(\v {\Gamma };E) = \frac {1}{\Omega (E)}\delta \left (H(\Gamma ) - E\right ), \end {equation} where now the \(\delta \)-function selects the surface of constant total energy \(E\). The superscript eq will be dropped in what follows, unless we want to make explicitly clear the distinction between equilibrium and nonequilibrium situations.

2.3.1 Entropy

A central concept in statistical mechanics is the entropy of a system. The general (nonequilibrium) entropy quantifies the number of microstates for a given phase-space density. It is defined as \begin {equation} S^\text {noneq}[\rho ] = -k_B\int d^{6N} \Gamma \rho \ln (\rho ), \label {eq:noneqentropy} \end {equation} where \(k_B\) is the Boltzmann constant. Note that the factor \(k_B\) has the role to turn temperatures from units of energy into units of \(K\); this will be discussed below. There is no fundamental physical reason to have \(k_B\) in Eq. \eqref{eq:noneqentropy}. Equation \eqref{eq:noneqentropy} is called the Shannon entropy in information theoretical contexts. Its construction is designed to have the following properties:

- The entropy is maximal for equal probabilities. We therefore find the equilibrium of a system by maximizing it. The principle of equal a priori probabilities is build into the entropy! This can be most easily seen by using a discrete phase space density, i.e. a set of probabilities \(\rho _\alpha \) for a discrete state \(\alpha \). The nonequilibrium entropy is then given by \begin {equation} S^\text {noneq} = \sum _\alpha \rho _\alpha \ln (\rho _\alpha ) \end {equation} which we now maximize. It is important to realize that the probabilities need to be normalized, \(\sum _\alpha \alpha =1\), and we hence need to maximize the entropy under this normalization constraint. This can be achieved by introducing a Lagrange multiplier \(\lambda \) and maximizing \begin {equation} S^\text {noneq} = \sum _\alpha \rho _\alpha \ln (\rho _\alpha ) + \lambda \left (\sum _\alpha \alpha -1\right ). \end {equation} This leads to the condition \(\ln (\rho _\alpha ) + 1 + \lambda = 0\) and hence \(\rho _\alpha = \text {const}\). A similar derivation applies for the continuous case.

- The entropy is not affected by the number of states with zero probability. All states with zero probably disappear from the integral/sum.

- The entropy is extensive, i.e. proportional to the size of the system. Consider two separate isolated systems \(A\) and \(B\) that can exchange neither energy nor particles and have individual entropies \(S_A\) and \(S_B\). Then the total entropy should be \(S = S_A + S_B\). We can describe each within their of phase space \(\v {\Gamma }_A\) and \(\v {\Gamma }_B\). This means we can define two independent phase space densities \(\rho _A(\v {\Gamma }_A)\) and \(\rho _B(\v {\Gamma }_B)\). The combined system lives in the combined space \(\v {\Gamma } = (\v {\Gamma }_A, \v {\Gamma }_B)\) and since they are independent, we can just multiply the probability densities to give \(\rho (\Gamma ) = \rho _A(\v {\Gamma }_A) \,\rho _B(\v {\Gamma }_B)\). The combined entropy is the given by \begin {align} \begin {aligned} S &= -k \int d^{6N_A+6N_B} \Gamma \rho _A \rho _B \ln (\rho _A \rho _B)\\ &= -k \int d^{6N_A} \Gamma _A d^{6N_B} \Gamma _B \rho _A \rho _B (\ln \rho _A + \ln \rho _B)\\ &= -k \int d^{6N_B} \Gamma _B \rho _B \int d^{6N_A} \Gamma _A \rho _A \ln \rho _A -k \int d^{6N_A} \Gamma _A \rho _A \int d^{6N_B} \Gamma _B \rho _B \ln \rho _B \\ &= -k \int d^{6N_A} \Gamma _A \rho _A \ln \rho _A - k\int d^{6N_B} \Gamma _B \rho _B \ln \rho _B\\ &= S_A + S_B \end {aligned} \end {align}

The equilibrium entropy for the microcanonical ensemble is \begin {equation} \label {eqn: eq_entropy} S^\text {eq}(E) =-k_B\int d^{6N} \Gamma \rho ^\text {eq} \ln (\rho ^\text {eq}) = k_B \ln \Omega (E) \end {equation} These are equal probabilities! Equilibrium maximizes the entropy.

Note that in the microcanonical ensemble the macrostate is characterized by the total energy \(E\). In general, we can use any type of constraint, representing our knowledge about the system, as a macrostate. The entropy then depends on the observer.

2.3.2 The ideal gas

The ideal gas is the simplest meaningful system that we can treat with these statistical methods. It also turns out to be one of the few systems that can be solved analytically. The Hamiltonian (total energy) of the ideal gas is \begin {equation} H(\{\v {r}_i\};\{\v {p}_i\}) = \sum _i \frac {\v {p}_i^2}{2m} \end {equation} i.e. there is just kinetic energy. For the sake of simplicity, the positional degrees of freedom \(\v {r}_i\) will be ignored in the following.

Let’s start by considering a few particles (or rather a few degrees of freedom) of identical mass \(m\). The statistics of the system will become useful for many degrees of freedom, but some concepts can be easily discussed in few dimensions. The phase space density for two degrees of freedom is \begin {equation} \rho _2^\text {eq}(p_1,p_2;E) = \pi ^{-1} \delta (p_1^2 + p_2^2 - 2mE) \end {equation} i.e. a circle. It is straightforward to see that this phase-space density is indeed normalized, \begin {align} \int dp_1 dp_2 \rho _2^\text {eq}(p_1,p_2;E) &= \pi ^{-1}\int dp_1 dp_2 \delta (p_1^2 + p_2^2 -2mE ) \\ &= 2 \int _0^\infty dp\, p \delta (p^2 - 2mE)\\ &= \int _0^\infty dp \, (-\delta (p+\sqrt {2mE})+\delta (p-\sqrt {2mE}))\\ &= 1 \end {align}

where we have used the \(\delta \)-function identity \(2x\delta (x^2-a^2) = -\delta (x+a)+\delta (x-a)\).

Having the combined probability density of both particles is usually not very useful. A useful quantity is the probability of finding particle \(1\) in momentum \(p_1\), irrespective of the state of particle two. This is a marginal probability density which we will denote by \(f_2(p_1;E)\) and it is obtained by integrating over all possible realizations of particle \(p_2\). It is given by \begin {align} \begin {aligned} f_2(p_1;E) &= \int dp_2\, \rho ^\text {eq}_2 (p_1,p_2;E) \\ &= \int _{-\infty }^\infty dp_2 \, \pi ^{-1} \delta (p_1^2 + p_2^2 -2mE )\\ &= \frac {1}{2\pi } \int _{-\infty }^\infty dp_2 \, \frac {1}{\sqrt {2mE - p_1^2}} \left [ \delta \left ( p_2 + \sqrt {2mE-p_1^2} \right ) + \delta \left ( p_2 - \sqrt {2mE-p_1^2} \right ) \right ] \\ &= \label {eq:marginaltwopart} \begin {cases} 0 & \text { if } |p_1| > \sqrt {2mE}\\ \pi ^{-1}(2mE-p_1^2)^{-\frac {1}{2}} &\text {otherwise} \end {cases} \end {aligned} \end {align}

where we have used \(\delta (x^2-a^2) = \frac {1}{2|a|}[\delta (x+a)+\delta (x-a)]\). Note that \(f_2(p_1;E)\) is normalized properly \begin {equation} \int dp_1 \, f_2(p_1) = \frac {1}{\pi } \int _{-\sqrt {2mE}} ^{\sqrt {2mE}} dp_1 \frac {1}{\sqrt {2E-p_1^2}} = \frac {1}{\pi } \int _{-1}^1 dx\, \frac {1}{\sqrt {1-x^2}} = 1. \end {equation}

This construction is not particularly useful for two degrees of freedom, but it is for many degrees of freedom. The equilibrium phase space density for an ideal gas of \(n\) degrees of freedom (usually \(n = 3N\) where \(N\) is the number of particles) is \begin {equation} \rho _n^\text {eq}(\{p_i\};E) = \frac {1}{\Omega (E)} \delta \left ( \sum _i p_i^2 - 2mE \right ) \end {equation} with \begin {equation} \label {eqn: phase_space_vol} \Omega (E) = \frac {\pi ^{n/2}}{\Gamma (n/2)} (2mE)^{n/2-1} \end {equation} being the total volume of the phase space. (Here \(\Gamma (x)\) is the Gamma function.) This is the surface area of a sphere of radius \(\sqrt {2mE}\) in \(n\) dimensions and the full expression is derived in Appendix 2.7!

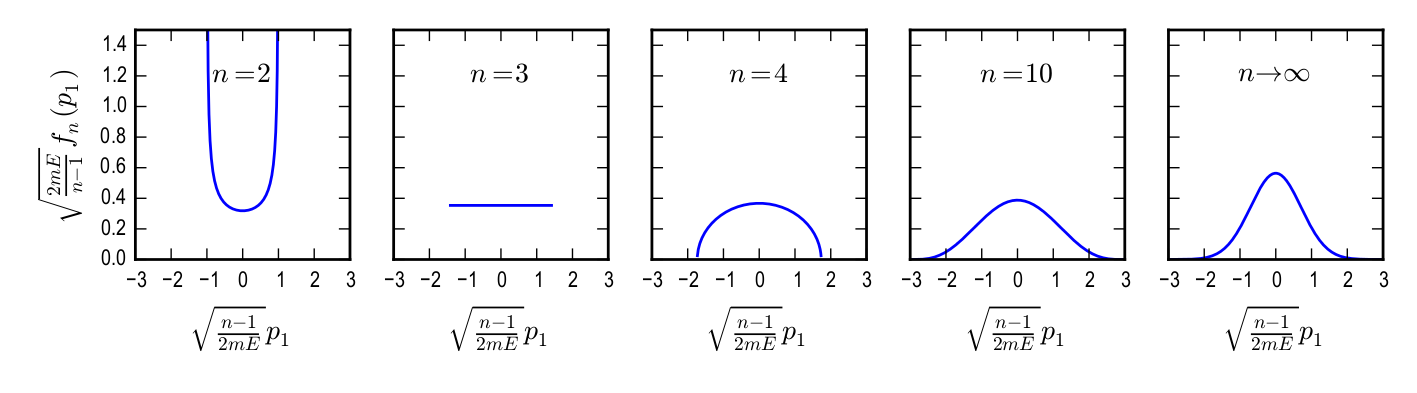

If we now integrate out all degrees of freedom \(p_2 ... p_N\) except for \(p_1\), we get the marginal distribution function \begin {equation} \label {eqn: marginal_distr_fun} f_n(p_1;E) = \int dp_2\ldots dp_n\, \rho ^\text {eq}_n (\{p_i\};E) = \frac {\Gamma \left (\frac {n}{2} \right )/ \Gamma \left (\frac {n}{2} -\frac {1}{2} \right )}{\sqrt {2\pi mE}} \left ( 1-\frac {p_1^2}{2mE} \right )^{\frac {n}{2} - \frac {3}{2}} \end {equation} For n = 2 this gives Eq. \eqref{eq:marginaltwopart} and the full derivation of Eq. \eqref{eqn: marginal˙distr˙fun} is given in Appendix 2.8. For illustration purposes, let us look at the expressions for \(n = 3\), and \(n = 4\). We find \begin {equation} f_3(p_1;E) = \frac {1}{\sqrt {8mE}} \theta (p_1^2 - 2mE) \end {equation} and \begin {equation} f_4(p_1;E) = \frac {2}{\pi } \frac {1}{\sqrt {2mE}} \sqrt {1- \frac {p_1^2}{2mE}}. \end {equation} It is straightforward to show (see Appendix 2.9, that in the thermodynamic limit \(N \to \infty \) (for a three dimensional space with \(n = 3N\)), Eq. \eqref{eqn: marginal˙distr˙fun} becomes \begin {equation} f(p_1;E) = \frac {1}{\sqrt {2\pi m (2E/3(N-1))}} \exp \left ( -\frac {p_1^2}{2m} \frac {3(N-1)}{2E} \right ) \end {equation} Now \(E/(N-1)\) is the kinetic energy per particle, i.e. \(2E/3(N - 1) = k_B T\). This is the probability distribution for each particle: \begin {equation} f(p_1;T) = \frac {1}{\sqrt {2\pi m k_B T}} \exp \left ( -\frac {p_1^2}{2mk_BT} \right ) \end {equation} The function \(f_3(p_1;E)\) simply constant over an interval of \(p_1\). \(f_4\) then peaks at \(p_1 = 0\), i.e. finding a particle with zero velocity has a maximum likelihood. The function the approaches a Gaussian in the thermodynamic limit \(n \to \infty \). The progression of the marginal distribution with \(n\) is shown in Fig. 2.1.

Note that the entropy for the marginal distribution function is given by \begin {equation} S(E) = -k\int dp_1\, f(p_1;E) \ln \left (f(p_1;E)\right ) \end {equation} The estimate Eq. \eqref{eqn: phase˙space˙vol} is not fully correct. First, it is missing the phase space volume of the positional degrees of free \(\v {r}_i\), but this integral is trivial to carry out and yield just \(V^N\) (where \(V\) is the volume).

The correct expression also needs to account for indistinguishability of the particles and includes a factor \(h^{3N} N!\) (\(N!\) is the number of possibilities \(N\) particles can be permuted and \(h\) is the Planck constant). This factor is called the Gibbs factor and has its origin in quantum statistical mechanics. It can be thought of as describing the quantization of the phase space volume. The correct number of states for the ideal gas is then \begin {equation} \Omega (E) = V^N \frac {\sqrt {2\pi m E/h^2}^{3N}}{N! (3N/2)!} \end {equation}

2.4 The canonical ensemble

2.4.1 Temperature, pressure, chemical potential

Assume two isolated subsystems with energy \(E_A\) and \(E_B\) (total energy \(E=E_A+E_B\)), volume \(V_A\) and \(V_B\) (total volume \(V = V_A + V_B\)) and particle numbers \(N_A\) and \(N_B\) (total particle number \(N = N_A + N_B\)). All of these quantities are extensive quantities, i.e. they scale with system size.

These systems occupy a phase space of volume \(\Omega _A(E_A,V_A,N_A)\) etc. and have entropies \(S_A(E_A,V_A,N_A)\). Now we let these systems exchange energy \(\Delta E\), volume \(\Delta V\) and particles \(\Delta N\), we equilibrate them. Note that we loose information when allowing these exchanges. Rather than knowing the Since we don’t know the configuration of the joint system, let’s find the entropy by maximizing it (remember, this is the equilibrium condition): \begin {equation} S_{AB}^\text {eq} (E,V,N) = \max _{E_A,V_A,N_A} S_{A}^\text {eq}(E_A,V_A,N_A) + S_{B}^\text {eq}(E - E_A,V - V_A,N - N_A) \end {equation} We find three equations that determine the equilibrium between the two systems, \begin {multline} \label {eqn: eq_TPmu} \frac {1}{T_A} = \frac {1}{T_B}\ \text { with }\ \frac {1}{T} = \frac {\partial S}{\partial E}, \frac {P_A}{T_A} = \frac {P_B}{T_B}\ \text { with }\ \frac {P}{T} = \frac {\partial S}{\partial V} \\ \text {and }\ \frac {\mu _A}{T_A} = \frac {\mu _B}{T_B}\ \text { with }\ \frac {\mu _A}{T_A} = \frac {\mu _A}{T_A} \end {multline} where we have identified temperature \(T\), pressure \(p\) and chemical potential \(\mu \).

Taking the entropy for the ideal gas above, we find for the temperature of the ideal gas \begin {equation} \frac {1}{T} = \frac {\partial S}{\partial E} = k \frac {\partial }{\partial E} \ln \Omega (E) = k \frac {3N}{2E} \end {equation} i.e. \(kT=2E/3N\).

2.4.2 The heat bath

Imagine a system \(A\) in contact with a much larger system \(B\), i.e. \(N_A \ll N_B\) and \(E_A \ll E_B\). Similarly to the ideal gas example above, we can integrate out all degrees of freedom of system \(B\). Indeed since \(B\) is just a heat bath, we can simply assume that it is a heat bath that is an ideal gas. It is then straightforward to show, that the marginal distribution function then becomes

\begin {equation} f(\{r_\alpha \},\{p_\alpha \};T) = \mathcal {P_A} \rho ^{eq} = Z(T)^{-1} \exp \left ( -\frac {H(\{r_\alpha \},\{p_\alpha \})}{kT}\right ) \end {equation} with \(kT = \frac {2}{3} \frac {E_B}{N_B}\) and the projection operator \begin {equation} \mathcal {P}_A \cdot = \frac {1}{N_A!} \int \prod _{\alpha \in B} dr_\alpha dp_\alpha \end {equation} The normalization factor \(Z(T)\) is called the partition sum and has a similar significance as the phase space volume \(\Omega (E)\), \begin {equation} Z = \int \prod _{\alpha \in B} dr_\alpha dp_\alpha \, \exp \left ( -\frac {H(\{r_\alpha \},\{p_\alpha \})}{kT} \right ) \label {eq:app-partition-sum} \end {equation} An alternative (and simpler) derivation of the canonical distribution function goes as follows. We know that in the microcanonical ensemble, the probability \(f(E_A)\) of finding subsystem \(A\) in with energy \(E_A\) must be proportional to \(\Omega _B(E-E_A)/\Omega (E)\), i.e. the probability of finding system \(B\) with energy \(E-E_A\). From Eq. \eqref{eqn: eq˙entropy} we can write this in terms of the entropy \begin {align} \begin {aligned} f(E_A) \propto \Omega _B(E-E_A) &= \exp \left [ \frac {S_B(E-E_A)}{k} \right ]\\ &\approx \exp \left [ \frac {1}{k} \left ( S_B(E) - \frac {\partial S_B}{ \partial E} E_A \right ) \right ] \end {aligned} \end {align}

where \(\approx \) holds for \(E_A \ll E \). From Eq. \eqref{eqn: eq˙TPmu} we can identify the derivative of the entropy as the temperature and get, \begin {equation} f(E_A) = Z(T)^{-1} \exp \left ( -\frac {E_A}{kT} \right ) \end {equation} The canonical ensemble makes it straightforward to see, that velocities should always follow a Gaussian distribution. If we use the classical Hamiltonian \(H(\{\v {r}_i\},\{\v {p}_i\}) = \sum _i \frac {\v {p}_i^2}{2m_i} + E_{pot}(\{\v {r}_i\})\), then \begin {multline} f(\v {p}_1) = Z^{-1} \exp \left ( -\frac {1}{kT} \frac {\v {p}_i^2}{2m_i} \right ) \int d^3r_1 \cdots d^3r_n d^3p_2 \cdots d^3p_N \\ \exp \left [ -\frac {1}{kT} \left ( \sum _{i=1}^N \frac {\v {p}_i^2}{2m_i} + E_{pot}(\{\v {r}_i\}) \right ) \right ] \end {multline} but the integral is just a constant.

We can estimate the expectation value of the temperature \(\langle k_BT \rangle \) and its fluctuations \(\langle (k_BT)^2 \rangle - \langle k_BT \rangle ^2\) from a canonical ensemble average. \begin {align} \langle k_BT \rangle = &\int _{-\infty }^\infty dp_1 \frac {p_1^2}{2m} \frac {1}{\sqrt {2\pi m k_BT}} \exp \left ( -\frac {p_1^2}{2mk_bT} \right ) = k_BT \\ \langle (k_BT)^2 \rangle = &\int _{-\infty }^\infty dp_1 \frac {p_1^4}{4m^2} \frac {1}{\sqrt {2\pi m k_BT}} \exp \left ( -\frac {p_1^2}{2mk_bT} \right ) = (k_BT)^2 \\ \end {align}

Hence \(\langle (k_BT)^2 \rangle - \langle k_BT \rangle ^2 = 0\). The temperature does not fluctuate in the canonical ensemble!

However the total energy does. We can estimate the energy fluctuations from the ensemble averages \(\langle H \rangle \) and \(\langle H^2 \rangle \), \begin {equation} \langle H \rangle = \frac {1}{Z} \int \prod _{\alpha \in B} dr_\alpha dp_\alpha H(\{r_\alpha \},\{p_\alpha \}) \exp \left (-\beta H(\{r_\alpha \},\{p_\alpha \}) \right ) \end {equation} where we have abbreviated \(\beta = 1/k_BT\). We can now use a mathematical trick to get \(\langle H \rangle \). Since \(H \exp (-\beta H) = -\frac {\partial }{\partial \beta } \exp (-\beta H)\), we have \begin {equation} \langle H \rangle = -\frac {1}{Z} \frac {\partial }{ \partial \beta } Z = -\frac {\partial }{ \partial \beta } \ln Z \end {equation} and \begin {equation} \frac {\partial ^2}{\partial \beta ^2} \ln Z = \frac {1}{Z} \frac {\partial ^2}{\partial \beta ^2} Z - \frac {1}{Z^2 } \left ( \frac {\partial }{ \partial \beta } Z \right )^2 = \langle H \rangle ^2 - \langle H^2 \rangle \neq 0 \end {equation} Hence energy fluctuates in the canonical ensemble.

2.5 The grand-canonical ensemble

The grand canonical ensemble allows exchange of particles in addition to exchange of energy. A possible derivation follow along the line of the one given above for the canonical ensemble, but allows for changes in number of particles \begin {equation} f(E_A,N_A) = \frac {1}{\mathcal {Z}} \exp \left ( - \frac {E_A-\mu N_A}{kT_B} \right ) \end {equation} Here \(\mathcal {Z}\) is called the grand-canonical partition function and \(\mu \) is the chemical potential from Eq. \eqref{eqn: eq˙entropy}.

2.6 Ergodicity

Ergodicity: “ The trajectory of almost every point in phase space passes arbitrarily close to every other point on the surface of constant energy.” [1] Note that two trajectories in phase space cannot cross, unless it is a periodic orbit.

This implies: Time averages equal microcanonical ensemble averages \begin {equation} \Bar {O} = \langle O \rangle \end {equation} where \begin {equation} \Bar {O} = \lim _{\tau \to \infty } \frac {1}{\tau } \int _0^\tau dt\, O \left ( \v {\mathit {\Gamma }} (t) \right ) \end {equation} This means we can compute ensemble averages from molecular dynamics trajectories, given our system is ergodic.

The statement \(\Bar {O} = \langle O \rangle \) implies that we can get the distribution function \(f( \v {\mathit {\Gamma }})\) that qualifies the ensemble from a dynamical run by computing the distribution during the time evolution, i.e. by treating each instant in time as its own independent realization of the system. We can therefore use a molecular dynamics run to compute \(f( \v {\mathit {\Gamma }})\). For example, the distribution of momenta \(f(p_1)\) is straightforwardly obtained even from single snapshots. Since all particles are indistinguishable, we can just use the momenta of all particles \(\v {p}_i\) as the random variables to construct \(f(p_1)\).

2.7 Normalization of the \(n\)-dimensional phase-space density

The normalization for \(n\) dimensions involves \(n\)-dimensional integrals. We have \begin {equation} \rho ^{eq} (\{p_i\};E) = \frac {1}{\Omega (E)} \int d^np\, \delta \left ( \sum _i p_i^2 - 2mE \right ), \end {equation} and, because of the normalization of the \(\int d^n\, \rho ^{eq}(\{p_i\};E) \equiv 1\), \begin {align} \begin {aligned} \Omega (E) &= \int d^np\, \delta \left ( \sum _i \frac {p_i^2}{2m} -E \right ) \\ &= S_n \int _0^\infty dp\, p^{n-1} \delta (p^2-2mE) \\ &= S_n\int _0^\infty dp \frac {p^{n-1}}{2\sqrt {2mE}} \left ( \delta (p+\sqrt {2mE}) - \delta (p-\sqrt {2mE}) \right )\\ &= \frac {1}{2} S_n \sqrt {2mE}^{n-2} \end {aligned} \end {align}

\(\Omega (E)\) is the volume of phase space occupied by the ideal gas at constant energy \(E\).

The prefactor \(S_n\) is the surface area of the unit sphere. We can find its value by a simple trick that involves integrals over Gaussians. Consider the following \(n\)-dimensional integral of a rotationally symmetric function, which we can carry out directly (because the \(n\)-dimensional Gaussian factorizes and the indefinite integral over a Gaussian can be carried out easily): \begin {equation} \label {eqn: n_dim_gaussian} \int d^nx\, \exp \left ( -\frac {1}{2} \sum _{i=1}^n x_i^2 \right ) = \left [ \int _{-\infty }^\infty dx\, \exp \left (-\frac {1}{2}x^2 \right ) \right ]^n = (2\pi )^{\frac {n}{2}} \end {equation} But using \(r=\sum x_i^2\) we can express this integral also as \begin {equation} \label {eqn: n_dim_gaussian_2} \int d^nx\, \exp \left ( -\frac {1}{2} \sum _{i=1}^n x_i^2 \right ) = S_n \int _0^\infty dr\, r^{n-1} \exp \left ( -\frac {1}{2} r^2 \right ) = S_n A(n) \end {equation} with \(A(n) = \int _0^\infty dr\, r^n \exp (-r^2/2).\) The substitution \(t=r^2/2\) gives \begin {equation*} A(n) = 2^{n/2-1}\int _0^\infty dt\, t^{n/2-1} \exp (-t) \equiv 2^{n/2-1} \Gamma (n/2) \end {equation*} where \(\Gamma (x)\) is the Gamma function. Note that \(\Gamma (n) = (n-1)!\) for integer \(n\). Hence we can equate Eq. \eqref{eqn: n˙dim˙gaussian} and \eqref{eqn: n˙dim˙gaussian˙2} to get \(2^{n/2-1} \Gamma (n/2)S_n = (2\pi )^{n/2}\), or \begin {equation} S_n = \frac {2 \pi ^{n/2}}{\Gamma (n/2)} \end {equation} Note that this gives \(S_2 = 2\pi \) (circle) and \(S_3 = 4\pi \) (sphere).

We therefore find the final expression for the phase-space volume \begin {equation} \Omega (E) = \frac {\pi ^{n/2}}{\Gamma (n/2)} (2mE)^{n/2-1} \end {equation}

2.8 Integrating out \(n - 1\) degrees of freedom

We follow the above procedure, but integrate out \(n - 1\) degrees of freedom. This gives the marginal distribution for finding particle 1 with momentum \(p_1\), \begin {align} \begin {aligned} f_n(p_1;E) &= \int dp_2 \cdots dp_n \rho ^{eq} (\{p_i\};E) \\ &= \frac {1}{\Omega (E)} \int d^{n-1} p \delta \left ( \sum _i p_i^2 -2mE \right ) \\ &= \frac {S_{n-1}}{\Omega (E)} \int dp\, p^{n-2} \delta (p_1^2+p^2-2mE)\\ &= \frac {S_{n-1}}{\Omega (E)} \int _0^\infty dp \frac {p^{n-2}}{2\sqrt {2mE-p_1^2}} \left [ \delta \left ( p + \sqrt {2mE - p_1^2} \right ) +\delta \left ( p - \sqrt {2mE - p_1^2} \right ) \right ]\\ &= \frac {1}{2} \frac {S_{n-1}}{\Omega (E)} \sqrt {2mE-p_1^2}^{n-3}\\ &= \frac {S_{n-1}}{S_n} \frac {\sqrt {2mE-p_1^2}^{n-3}}{\sqrt {2mE}^{n-2}} \\ &= \frac {1}{\sqrt {2\pi m E}} \frac {\Gamma (\frac {n}{2})}{\Gamma \left ( \frac {n}{2} - \frac {1}{2} \right )} \left ( 1-\frac {p_1^2}{2mE} \right ) ^{\frac {n}{2} - \frac {3}{2}} \end {aligned} \end {align}

2.9 The thermodynamic limit: Integrating out \(3N \to \infty \) degrees of freedom

We have until now only considered \(n\) degrees of freedom. For \(N\) particles moving in three dimensions, \(n = 3N\). The limit of large particle numbers, \(N \to \infty \), is called the thermodynamic limit. The marginal distribution function for \(N\) particles is \begin {equation} f_{3N}(p_1;E) = \frac {\Gamma \left ( \frac {3N}{2} \right ) / \Gamma \left ( \frac {3N}{2} - \frac {1}{2} \right )}{\sqrt {2\pi mE}} \left ( 1- \frac {p_1^2}{2mE} \right ) ^{\frac {3}{2}(N-1)} \end {equation} WE now use the identity \(\lim _{n \to \infty } (1+x/n)^n = e^x\) and \(\Gamma \left ( \frac {n}{2} \right )/ \Gamma \left ( \frac {n}{2} - \frac {1}{2} \right ) \approx \sqrt {(n-3)/2}\) for large \(n\) to obtain (in the thermodynamic limit) \begin {equation} \label {eqn: marg_distr_therm} f(p_1;E) = \sqrt {\frac {3(N-1)}{4\pi m E}} e^{-\frac {p_1^2}{2m} \frac {3(n-1)}{2E}} \end {equation} Note that the total energy \(E\) is an extensive quantity, \(E \to \infty \) as \(N \to \infty \). However, the only quantity that shows up in the Eq. \eqref{eqn: marg˙distr˙therm} is \(E/(N-1)\). With the temperature \(3k_BT/2 = E/(N-1)\), hence \begin {equation} f(p_1;T) = \frac {1}{\sqrt {4\pi m k_B T}} e^{-\frac {p_1^2}{2mk_B T}} \end {equation} Note that \(3k_B T/2 = E/(N - 1)\) rather than \(3k_B T/2 = E/N\) because the movement of the center of mass of all particles does not contribute to the temperature.